Sometimes, the Supreme Court of Canada breaks new ground. Sometimes, it confirms stuff that everyone has thought for a long time, but there is a surprising lack of authority for. I was taught that "litigation privilege" or "solicitor brief" privilege was different from "solicitor-client privilege", and ends when litigation does instead of lasting forever, but there was surprisingly little law that says so. Now there is.

All professions (priests, doctors, probably engineers and beauty technicians) hate revealing confidential information that flows between themselves and their clients. Lawyers, no doubt because they control the law, have been most effective at creating an absolute rule that they don't have to. That's called solictior-client privilege. It doesn't matter how socially valuable or logically probative it would be to reveal what a lawyer said to a client or vice versa -- the law does not allow it.

Litigators also hate telling people stuff they have found out trying to work up a case (unless it works for their side), even if it is just a newspaper clipping they found or the opinions of an expert they consulted. This kind of makes sense, since lawyers would be more careful about finding stuff out if it came back on them later. But it really isn't the same thing as confidential disclosures directly between the client and the lawyer.

And so the court has held. Mr. Blank (if that is his real name) has been fighting the DOJ for a long time about a Fisheries Act prosecution they brought against him in the mid-1990s and then stayed before trial. Civilly suing for unsuccessful prosecutions is difficult in Canada, but Mr. Blank has stuck with it, and will no doubt go down in the annals of in-person litigants for this one. He filed to get the Crown brief under the Federal Access Act to Information Act, which, like all Freedom of Information statutes, provides for an exception to the general rule of disclosure when the documents are "solicitor-client privileged."

As a statutory matter, the Court accepts that, given that the statute was written before their judgment, "solicitor-client privilege" in the Access Act incorporates what they now want to call "litigation privilege." But it only lasts until the proceedings giving rise to the privilege, and all "closely related proceedings" have ended. That latter exception is going to give rise to some fighting down the road, but that's how it is.

I would praise this thing unreservedly were it not for Part V of Justice Fish's judgment, which goes on about whether litigation privilege exists when the "dominant" purpose of obtaining the information was litigation or when it was just a "substantial purpose." Fish admits this has nothing to do with the case before him. He should have just shut up about it. Clerks need to learn that some of their research is going to be thrown away. It is an abuse of judicial power to engage in these obiter forays, particularly when they are clearly intended to bind lower courts. Similarly, Justice Bastarache's concurrence was undisciplined and unneccessary.

Case Comment of Blank v. Canada (Minister of Justice), 2006 SCC 39.

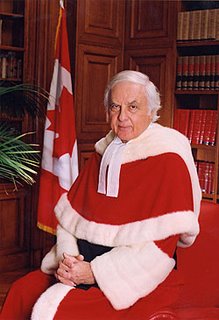

Photo credit: Phillipe Landreville, Supreme Court of Canada collection

Update: Welcome to everyone who followed the link from Colby Cosh. It is quite an honour: it was Mr. Cosh's challenge to the Canadian legal profession that inspired me to devote my procrastiantion hours to this thing. So far, everyone's been very good about my defeatist, anti-American loony left political leanings.

No comments:

Post a Comment